I must confess that Revelation has not always been my favorite book in Scripture. I can distinctly remember a time before I went to seminary in which I imagined that perhaps one of the things that pastors learned when they earned a Master’s of Divinity degree was how to understand (and then preach/blog about!) books such as this. And it seemed I wasn’t the only one who had mixed views on this last chapter of the Biblical narrative. Many different Christians I talked to who were otherwise well-versed in Scripture appeared to be unfamiliar and even uncomfortable with Revelation. On the other hand, there were Christians who appeared to devote an inordinate amount of their devotional and theological interest to this one book, and unlocking its “secrets.”

In subsequent years however I’ve fortunately had the chance to learn to appreciate and absorb the teachings of Revelation better. I’ve heard some great teaching on its contents from David Platt and my pastor at my home church in Alabama, Jay Wolf. Back when he was still pastor of the Church at Brooke Hills, Platt did an extensive teaching series on Revelation, with the verse-by-verse detail and expositional expertise that is his trademark. One of the biggest takeaway points I remember from the series was Platt’s emphasis that Revelation is a book meant to unite, rather than divide the church. This is certainly an important truth to keep in mind, because historically Christians have sometimes drawn theological and denominational “battle lines” around where they stood on the interpretation of certain portions of Revelation such as the Millennium or the extent to which the book’s prophecies referred to past, present, or future events. To this point, I’ll add two other observations from Jay Wolf, who like David Platt wished to emphasize how Revelation could bring the church together rather than provide fodder for argumentation or fruitless eschatological speculation. Jay has said that Revelation should “drive us to Christ, not to charts”, a quasi-humorous reference to the complicated nature of some of the teaching therein, which has led some theologians and scholars to try and approach it from a visual, or schematic standpoint. But the underlying message is a serious one, that the Body of Christ should use God’s Word to find common ground and mutual encouragement, whenever possible. Jay also is fond of giving his two-word summary of Revelation’s contents as follows: “Jesus wins.” Indeed, the ultimate victory of Christ is the salient point to be taken away from Revelation, and if we lose sight of that critical truth, much of our additional study of this unique book will lose its proper focus and emphasis.

There are many extensive and exhaustive commentaries and companions to Revelation that I could bring into my discussion for the remainder of this blog post. But sometimes, less can be more, and I want to highlight one relatively brief commentary that I have found particularly enjoyable and accessible, Richard Bauckham’s The Theology of the Book of Revelation.[1] I first used this commentary in seminary, and revisited it recently for my own personal study. Some of the insights I gained were so valuable for my understanding of Revelation that I wanted to share them here. I’ve always envisioned my blog not only as a reflection of my ministry experiences, and personal insights I’ve gleaned from ministry, the Scriptures, and trying to pursue the Christian walk, but also to be a place where I could pass on the wisdom of others. I will freely admit that while I did have the opportunity to study a great deal about Biblical interpretation and exegesis at seminary, Revelation is a book whose complexity calls for bringing in some outside aids. I believe Bauckham has produced a readable yet still intellectually rigorous introduction to the spiritual riches of the Book of Revelation, while containing his observations within a relatively compact volume of 164 pages. It is clear from his writing that he still takes Biblical authority seriously, and is not simply approaching his work from a detached, scholarly standpoint, but rather through a lens of faith. In addition, he structures his arguments thematically, rather than in an expositional, or verse-by-verse format. As a result, Bauckham’s work encourages the reader to see more of the “big picture” concentrating on the timeless and significant themes of Revelation rather than getting caught up in the details of trying to interpret each individual verse, symbol, or prophecy. I want to reflect on just a few highlights of his work that have been personally very beneficial for me as I seek to better understand this important Scriptural text. While this will of course in no way attempt to be an exhaustive or systematic trip through Revelation, my hope is that with some further study, the book will appear a little less mystifying and will fit better into the context of the rest of Scripture. Perhaps most importantly, you’ll see that Revelation is full of practical wisdom and applicability to Christians in 2016.

As Bauckham reveals early in his book, one of the reasons that people have historically struggled to properly understand Revelation, is because they have misunderstood its genre. Revelation is often referred to as a “prophetic” or “apocalyptic” text, while other people may be most familiar with its first three chapters, which feature seven letters to different churches in Asia Minor. Revelation in fact represents a unique blend of three different types of Biblical literature—prophetic, apocalyptic, and letter. These genres are at times distinctive within the overall book but often are also intertwined together. A brief explanation of each genre’s place within Revelation may be helpful. It is a prophetic book not only because God is revealing His Word and teachings directly to the author John, but also in the way that Revelation builds extensively on tropes and traditions drawn from the Old Testament tradition, including many of the prophetic books. In addition it is addressing a specific historic situation, namely that of churches in the Asian provinces of the Roman Empire towards the end of the first century AD. Many people automatically associate the adjective “prophetic” with a foretelling of future events, and while Revelation does contain some of this type of prophecy in the broad sense, we should be careful of trying to define too specifically the types of events that may occur based on our reading or interpretation of the text. As Bauckham writes, “Revelation has suffered from interpretation which takes its images too literally. Even the most sophisticated interpreters all too easily slip into treating the images as codes which need only to be decoded to yield literal predictions. But this fails to take the images seriously as images. John depicts the future in images in order to be able to do more and less than a literal prediction could. Less, because Revelation does not offer a literal outline of the course of future events…but more, because what it does provide is insight into the nature of God’s purpose for the future.” (p.93). Revelation can be termed apocalyptic literature in that in offers us insight from a transcendent, Divine perspective, a God’s-eye view of history and events. The author, John, has a heavenly, other-worldly experience from which he draws the information and imagery that is then revealed to the reader. Finally, just as we see in other parts of the New Testament, most notably in the writings of Paul, Revelation contains letters. While chapters 1-3 include letters to seven historical churches in Asia Minor, the full impact of these teachings is designed of course to serve the benefit of the entire church. The seven churches are each struggling with different doctrinal and theological issues that in effect cover the spectrum of possible situations that Christians of that day might have faced, and still confront in the present. Just then as with the epistles of Paul, the letters in Revelation can both enable us to better understand the historical context of the problems faced by a church in a particular moment of history, and also serve as timeless sources of Scriptural instruction that remain relevant for believers today.

As we think about Revelation as a whole, it’s also important to reflect briefly on its title. Sometimes mistakenly called “Revelations” the singularity of the book’s name is crucial, because its 22 chapters represent one unified message and narrative. Also, for all of the difficulty and controversy that has sometimes surrounded the proper interpretation and application of its contents, Revelation’s message was never intended to be “secret.” Revelation 22:10 clearly states this: “And he said to me, ‘Do not seal the words of the prophecy of this book, for the time is at hand.” Often you will see commentaries, studies and guides for Revelation which promise to “unlock”, “decode”, or “unveil” its message. But the fact of the matter is that the book’s message is not meant to be hidden away, or kept secret from all but the select few with the knowledge to understand it. Yes, there are symbols and imagery that must be investigated and better understood, but their apparent inaccessibility to the uninitiated reader is much more a function of the gulf in time and space between our culture in the America of 2016 and the cultural situation of the 1st century AD in the Ancient Near East. It does not stem from the author of Revelation’s intent to deceive, mystify or somehow hide his message from anyone. Imagine a time traveler from centuries in the future suddenly arriving in our present day and perusing political cartoons in a local newspaper. They might be initially stumped by caricature depictions of Trump and Hilary Clinton, or the Republican elephant and the Democratic donkey. However any one of us would readily understand these symbols and their interpretive meaning, perhaps without even needing to read the captions of the cartoon. In a similar fashion, the initial contemporary audience of John’s teaching would have understood many of the images he used instinctively, so as Christians in 2016 we need to recognize that our lack of understanding of Revelation is not formulated on any attempt by the author to keep his meaning hidden, but a function of these cultural and historical differences, which can be bridged in large part through Scriptural study. Adding to this, Bauckham notes of the symbology in Revelation: “once we begin to appreciate their sources and their rich symbolic associations, we realize that they cannot be read either as literal descriptions or as encoded literal descriptions, but must be read for their theological meaning and their power to evoke response.” (p.20).Knowing then that Revelation is not meant to be in any way a “secret” teaching should reinforce our belief that is has a message designed to bring the church together, rather than split it into factions based on who can properly understand these teachings. Nonetheless, while Revelation conveys this message of unification, it also carries a message of judgment, which we will discuss in further detail a little later. Now sometimes the book is summarized as being solely designed to provide comfort to Christians who were beginning to suffer increasing persecution under the auspices of the Roman Empire. While it certainly does have this function, Revelation is also a book which challenges Christians who have become complacent and comfortable under imperial rule to the point where they are willing to compromise their beliefs in order to not challenge the status quo. Such aims of the author are not contradictory however but rather complementary in the sense that they further earmark Revelation as a prophetic text which will “comfort the afflicted, and afflict the comfortable.”

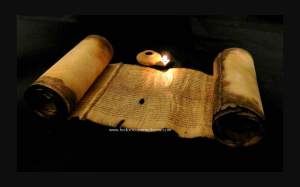

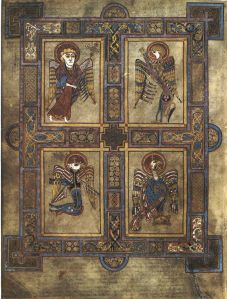

If we were to summarize the overall message given to the seven churches in Revelation 1-3 it would be this: “be victorious!”, and “don’t compromise!” While each church faces specific theological challenges, the hope is that they will be faithful to God, rather than allowing either persecution or their own comfortable co-existence within the Roman system to cause them to damage or lose their witness as Bodies of Christ altogether. Then, in Revelation chapter 4, we get a glimpse into the Throne Room of Heaven, part of the otherworldly perspective that the unique apocalyptic focus of this book can offer. God’s sovereignty is here made manifest, and plainly acknowledged as it will be in the future all across the earth. The Throne Room scene also offers some interesting usage of Old Testament symbols which are now slightly re-envisioned. For example, the Divine Throne is surrounded by four living creatures, reminding us of the cherubim that flanked the Ark of the Covenant, and the heavenly creatures described in Ezekiel 1. Incidentally, these four living creatures, described as having the appearance of a lion, calf, man, and eagle have traditionally been used to symbolize the four Gospels: Mark, Luke, Matthew, and John, respectively. Again and again in Revelation, we see the appearance of Old Testament symbols which gain a new interpretive power in the context of their usage in this book. Thus the sealed scroll described in Revelation 5 and the sealed book which John is told to eat in Revelation 10 have their Old Testament counterparts in the scroll the prophet eats in Ezekiel 3.

Significantly too, the imagery in Revelation maintains an overall harmony and consistency with the Old Testament. So, just as throughout the Old Testament we never see the face of God directly, Revelation also resists in any way anthropomorphizing the person of God the Father—that is presenting Him in human form. Thus while images of judgment, thrones, and crowns might conjure up human ideas of monarchy, as Bauckham mentions, the goal of the author is actually to convey a totally opposite and other conception of God that is non-human: “John’s purpose is certainly not to compare the divine sovereignty in heaven with the absolute power of human rulers on earth. Quite the contrary: his purpose is to oppose the two…the imagery purges it of anthropomorphism and suggests the incompatibility of God’s sovereignty.” (p. 43.). Furthermore, Bauckham perceptively points out that how the insistence in Revelation on an otherworldly, transcendent God does not make Him any less close to humanity, but actually can serve to increase His immanence, and nearness to us: “Transcendence requires the absolute distinction between God and finite creatures, but not at all His distance from them. The transcendent God, precisely because He is not one finite being among others, is able to be incomparably present to all, closer to them than they are to themselves.” (p. 46). Revelation also reinvigorates another conception of God that goes all the way back to the beginning of the Biblical narrative in Genesis, that of God as Creator. Part of the great hope that the book offers us is the promise that God will not simply preserve the faithful in the face of persecution or amidst the tribulation of the End Times, but that He will actively recreate both heaven and earth, thus perfecting what, in the case of earth, had previously been marred by sin and the effects of the Fall. This is the great truth inherent in Revelation 21:1—“Now I saw a new heaven and a new earth, for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away. Also there was no more sea.” The reference to the disappearance of the sea in 21:1 is highly significant as well. The ancient Israelites, not being a sea-faring people, tended to view the ocean as a place of mystery and fear. It was where legendary monsters dwelled, such as the Leviathan mentioned in Job. In the Genesis creation account, God’s spirit had brought order to the primeval chaos of the waters. These same waters had of course later flooded over the earth in judgment, save for Noah and his family in Genesis 6. So God’s final destruction of the sea in Revelation 21 signifies on multiple levels the ultimate Divine victory. The sea’s absence means there will no longer be anything hidden or unknown, and at the same time God is declaring that His Creation is now eternally secure against the threat of destruction.

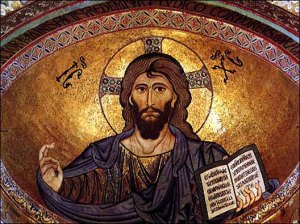

The immanence of the Divine presence is of course also distinctly communicated to the church and the faithful through the person of Christ. And make no mistake, Jesus is a very central figure in this book. In fact one of the hallmarks of the text is its high Christology, comparable to that found in the Gospel of John. And interestingly enough, despite this emphasis on Jesus’ clear identity as the Messiah and One who is equal to God, Revelation, as we have already alluded to, features a strong Jewish identity through its many references to Old Testament prophets and themes. As Bauckham explains: “the worship of Jesus was part of early Christian religious practice from a relatively early date and it developed within Jewish Christianity where consciousness of the connection between monotheism and worship was high. It cannot be attributed to Gentile Christian carelessness of the requirement of monotheistic worship. It must be regarded as a development internal to the tradition of Jewish monotheism, by which Jewish Christians implicitly included Jesus in the reality of the one God.” (p.61). Some religious scholars will try to argue that the worship of Christ was only added later as more Gentiles came into the church, but here Bauckham strongly contends that these largely Jewish Christian communities nonetheless understood and viewed Christ as equal to God. This is a good response to the argument made by Bart Ehrman and other liberal religious scholars that Jesus was only elevated to the status of God much later in history. As an interesting grammatical side-note on the topic of Revelation’s Christology, Bauckham notes how in the original Greek, the author John often uses a singular verb or a singular pronoun when referring to God and Christ together. This is perhaps a further clue to his view that they are co-equal and indeed One.

As for Christ’s role within the Book of Revelation, there are several images used in the text to convey different aspects of Christ’s power and purpose. In Revelation 1:17, Christ refers to Himself as “the first and the last.” This brief phrase is full of symbolic importance, demonstrating as it does how Christ was present both at the beginning of Creation as a member of the Trinity, and how His return will usher in the end of history. It can remind us also of the description of Christ as the Word provided in John 1:1—“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” Then in Revelation 5, Christ appears as the Lamb. This is of course an image of sacrifice, reminding us of Jesus’ willing death for the sins of all humanity, and again reminiscent of earlier passages from the Gospels, namely John 1:29—“The next day John saw Jesus coming toward him, and said, ‘Behold! The Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world.” We can think too of the sacrificial Passover Lamb of Exodus 12. Jesus is also viewed in Revelation as the fulfillment and culmination of the many Messianic prophecies found in the Old Testament. Thus in Revelation 22:16, Christ offers this self-description: “I am the Root and the Offspring of David, the Bright and Morning Star.” Among the many prophecies that this verse makes reference to is one found in Numbers 24:17. Jesus appears as the fearsome conquering Messiah in Revelation 19, whereas similar language can also be found in Isaiah 11. Christ’s role in Revelation is also that of a faithful witness. He is referred to in Revelation 1:5 and 3:14 as the “faithful and true witness.” His willingness to be sacrificed for the Truth of His witness is reflected by the similar faithfulness unto death demonstrated by His followers. The Greek word “martyr” literally means “witness” and while in Revelation the faithful witnesses of Christ do not necessarily always incur death as a result, it is clear from the narrative that they, and indeed all Christ followers should be prepared to be faithful even to death. The Two Witnesses described in Revelation 11 are thus symbolic of all those who follow in the model and footsteps of Christ, and are prepared to testify to the Truth of the Gospel, regardless of the penalties this might bring from the oppressive forces of the Empire and evil. The Two Witnesses are eventually put to death, and yet their Resurrection in Revelation 11:11 reflects of course the Resurrection of Christ, and is proof that the forces of oppression will never be able to permanently stop the spread of the Word of God.

Speaking of opposition to the God’s Word and work, Revelation is famed for the fearsome images it evokes of the enemies of God’s people. The three most significant are what Bauckham terms the “satanic trinity”, which includes the dragon/serpent, the sea-monster beast, and the earth-monster beast. The dragon appears in Revelation 12, as well as later in Revelation 20:2 as the creature confined by the angel into the bottomless pit. This dragon or serpent is equated in Revelation 12:9 and in 20:2 with Satan, and of course we can think back all the way to Genesis 3, and identify it equally with the serpent who tempts Adam and Eve to sin in the Garden of Eden. The connection with the Genesis narrative is further strengthened by the content of Revelation 12. Here, a woman gives birth to a son, and then is immediately pursued by the vengeful dragon. The woman flees into the wilderness to a place of sanctuary prepared for her by God, while the son is taken up to heaven. This victory of the woman and her offspring even in the face of persecution from the dragon, who literally represents evil incarnate, confirms the prophecy found back in Genesis 3:15. There, God pronounces this curse upon the serpent: “I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your seed and her Seed. He shall bruise you head, and you shall bruise His heel.” The woman then can symbolize Eve, the first mother as well as later Mary, the Mother of Jesus, while the Son is Christ, whose sacrificial death will be the bruised heel, but who will permanently destroy the head of evil. The two beasts meanwhile, also have their Old Testament antecedents. The sea-beast a continuation of the concept of the Leviathan, a primeval sea monster, and the Behemoth, a gigantic land creature, are both mentioned in the Book of Job. In the Book of Revelation, these primeval monsters are transformed into symbols of imperial Roman power. The sea-monster represents the military might of Rome, while the earth-monster symbolizes the propaganda machine of the imperial cult. While it would appear in Revelation 13:7 that the beasts are able to overcome the faithful by slaying them, it is in fact the very death of these martyrs and witnesses to Christ that ensures their final victory. As Bauckham shares: “When the martyrs testify to the true God against the spurious divine claims of the beast and refuse to admit the lies of the beast even when they could evade death by doing so, they win the victory of truth over deceit. The beast’s lies cannot deceive them or even win their lip-service by coercion. He can kill them, but he cannot suppress their witness to the truth.” (p.91). Moreover, in this critical confrontation between good and evil, John wants his readers to know that everyone has a part to play. The decision as to whether someone will side with the Empire’s ostensibly invincible might and the worldly rewards it can offer, or stand for the power of God’s unquenchable truth and its heavenly inheritance is one that Christians today still must confront.

Then, in Revelation 17, another important symbolic enemy is introduced—the Great Harlot, also called Babylon. The city of Babylon and its associated empire was of course formerly one of the great enemies of the Jewish people, responsible for the destruction of the Southern Kingdom of Judah in 586 BC, and subsequently the site of a long period of exile for many Jews. It was now a symbol and essentially a code word for the current great Empire and enemy—Rome. The image of a harlot or whore not only conjures up unfaithfulness, and the worship of many different gods (thus a kind of religious “promiscuity”—the opposite of a strict monotheism), but also is a commercial image that reminds readers of the formidable economic clout of the Roman Empire. Interestingly, whereas Christians are called to defeat the two beasts, they are called to escape Babylon, as Revelation 18:4 attests: “And I heard another voice form heaven saying, ‘Come out of her, my people, lest you share in her sins, and lest you receive of her plagues.” Just as the beasts are defeated by the faithfulness of Christian witnesses unto death, we eventually witness the fall of Babylon in Revelation 18 as a judgment and Divine censure from God.

Other imagery within Revelation is often associated with numbers. One of the most famous examples is of course 666, the Number of the Beast, from Revelation 13:18. Six is the number of man (who was created on the Sixth day, along with land-dwelling animals). It is one short of seven, the heavenly number of perfection. There is plenty of symbolic importance here without having to necessarily translate through numerological analysis the meaning of the number, which some Biblical scholars have assigned as a coded reference to Nero, Domitian or another hated Emperor of the Imperial Roman regime. Also, there is a series of different judgments, fearful in their content, and severity, which come in sevens. As we have mentioned, seven is the heavenly number, the number of fullness and completion. So in this case, we can know that the judgments described—the seven seals, seven trumpets, and seven bowls, all symbolize that God’s wrath has reached its climax and is being fulfilled upon those who have repeatedly refused to repent. Other numerical associations in Revelation include the number 12 and variations of it. Twelve of course symbolizes the Twelve Tribes of Israel, showing that connection between God’s original Covenant with Israel, and His final plan for the redemption of all humanity through the Messiah from Jewish lineage—Jesus. In the Heavenly Throne Room scene in Revelation 4, we see 24 elders gathered around the Divine Throne—a multiple of twelve. Later, in Revelation 7, the Messianic fulfilment of Christ’s work is symbolized by the sealed group of 144,000, meaning 12,000 from each of the Tribes. Finally, at the end of Revelation, we can read descriptions of the New Jerusalem, which will now be the Holy City not only for the Jews, but for the redeemed of all humanity. It contains 12 gates, while in its midst is a Tree of Life (a perfect redemption of that Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil which symbolized humanity’s sin and downfall in Genesis 3).

The ultimate mode of Divine triumph and the completion of God’s work in history will take place through the event of the Parousia, the Second Coming of Christ. Many Christians who’ve studied Revelation have tended to fixate their interest on this aspect of the book, and specifically on trying to ascertain the exact particulars of Christ’s Return and the events thereafter. But of course as we are reminded by Matthew 24:36, no one, not even the angels, knows the exact day or hour of Jesus’ Return. Thus, for Bauckham, our focus when considering the End Times and the exact chronology of events should be more directed towards who will triumph rather than how or when exactly that triumph will unfold. Revelation assures us of the final victory of the forces of righteousness with Christ at their head, as chapter 19 describes. In Revelation 20 we see that Satan is bound for 1000 years, and the nature of this Millennium, as well as the events which take place thereafter has been the source of much theological debate over the centuries amongst Christians. Bauckham sidesteps much of the discussion over Premillennialism, Postmillennialism, and Amillennialism, to instead direct attention to what he feels is the main message of the teaching: “the theological point of the millennium is solely to demonstrate the triumph of the martyrs: that those whom the beast has put to death are those who will truly live eschatologically, and that those who contested his right to rule and suffered for it are those who will in the end rule as universally as he—and for much longer: a thousand years!” Taken as a spiritual symbol, the Millennium confirms then the triumph of the faithful of Christ, the very ones the Beast had sought to destroy. Yet, as Bauckham points out, attempts to translate the Millennium onto a literal timeframe end up causing more problems, and raising more questions than is necessary: “We then have to ask all the questions which interpreters of Revelation ask about the millennium but which John does not answer because they are irrelevant to the function he gives it in his symbolic universe…Whom do the saints rule? Do they rule from heaven or on earth? How is the eschatological life of resurrection compatible with an unrenewed earth?…The millennium becomes incomprehensible once we take the image literally…John expected the martyrs to be vindicated, but the millennium depicts the meaning, rather than predicting the manner of their vindication.” (p.108). Bauckham then falls in the Amillennialist camp, as did many of the early church fathers such as St. Augustine, and prominent leaders of the Reformation like Martin Luther and John Calvin. If you are interested in more detail about this particular theological stance, Wikipedia actually has a good summary page. But basically the Amillennialist position says that the Millennium as described in Revelation 20 is not a literal 1000 year period, but rather symbolic in nature, and yet it still definitely affirms there will be a literal Return of Christ at some unknown date in the future. But since no Christian can claim to know with any degree of certainty the exact time of Christ’s Return, perhaps as a Church our focus should be more on the meaning of these Final Things, rather than the manner in which they will take place. Thus back to Jay Wolf’s wonderfully succinct summary of the essence of Revelation’s message: “Jesus wins!”

This leads to the last chapter from Bauckham’s book I want to discuss—“Revelation for today.” It would be a great tragedy if Revelation were only seen as a book focused either on yet-to-occur events of the future, or was merely a historical relic which had bolstered the strength and resolve of early church leaders facing martyrdom at the hands of a ruthless imperial system. Revelation, like all books in the Biblical Canon, contains great relevance and applicability to the lives of believers today. The power of the book really lies in the wonderful diversity of images and messages it conveys. Near the outset of this blog post we discussed how Revelation presents a unique mixture of different Biblical genres: prophetic, apocalyptic, and letter. And in the mixture of these different genres, we receive messages that at times would seem to be almost in opposition to one another, and yet actually blend together neatly in the final analysis. God’s wrath is certainly on display in the book, through a series of fearful judgments, and yet perhaps nowhere else in Scripture is His love for His people more tenderly displayed than in Revelation 21:4, where we are told “God will wipe away every tear from their eyes, there shall be no more death, nor sorrow, nor crying”. Indeed, at the conclusion of Revelation, the God who has been hidden beforehand, working through symbols, and heavenly messengers, is now directly present in a way that was never before possible in the Biblical narrative. Revelation 21:3—“Behold the tabernacle of God is with men, and He will dwell with them, and they shall be His people.” The glorious New Jerusalem that is described in Revelation 21 and 22 has no need for the sun or the Temple, because God’s magnificent presence illuminates everything and He is perfectly accessible to all who dwell in that blessed heaven. Revelation has also perhaps confused some readers with its seemingly contrasting themes of Christ’s imminent Return, and the apparent delay in the occurrence of many of the events described in the book. Certainly there is a sense of urgency and imminent expectation that runs throughout the book. John opens his narrative by referring in Revelation 1:1 to “things which must shortly take place.”, while Jesus’s last words in Revelation 22:20 are “Surely I am coming quickly.” And yet at the same time, the martyrs who in 6:10 cry out “How long, O Lord?” are told to wait a little longer, and there is a symbolic period of three-and-a-half years during which God stays His Hand concerning future judgments while the Two Witnesses continue to preach in Revelation 11. Yet we know too from elsewhere in Scripture that we must be careful in thinking that God is “delaying” when such calculations usually say more about our own human timeframe than any Divine chronology. 2 Peter 3:8-9 reminds us of this truth: “But beloved, do not forget this one thing, that with the Lord one day is as a thousand years, and a thousand years as one day. The Lord is not slack concerning His promise, as some count slackness, but is longsuffering toward us, not willing that any should perish but that all should come to repentance.” These verses are a good indicator of what is at work in the Book of Revelation as well. God’s delay, if we can call it that, is based in part on a desire to give as many people as possible the opportunity to find repentance in Christ before some of these Final Judgements come to pass. Ultimately, for both the original audience of John’s writings, and Christians in 2016, the study of Revelation invites us to wrestle with hard questions—not about the detail of particular symbology or chronology, but overarching, universal questions such as will we compromise with our culture, or resist faithfully?? What if our material prosperity and even our lives are threatened in the process? And knowing that Jesus’ final victory is assured, why aren’t we living with more purpose, conviction, and confidence as Christ followers in the here and now?? What part will we play in helping to prepare the world around us for the Return of the King? All of these questions are just as fresh, relevant, and pressing for us in 2016 as they were for believers of the first century AD, and Revelation can serve as a wonderful guide for us to think about how we will respond in a manner that is Biblically faithful.

Revelation, in the final analysis, is not a complicated “code” to invite argument over theological detail, nor a consolation reserved for some far-off future, nor an incomprehensible jumble of apocalyptic detail to be fearfully avoided. Rather, as Bauckham eloquently attests, it is a call to action for all believers, then and now! “Revelation does not respond to the dominant ideology by promoting Christian withdrawal into a sectarian enclave…while consoling itself with millennial dreams…Revelation’s outlook is oriented to the coming of God’s Kingdom in the whole world and calls Christians to active participation in the coming of the kingdom. It its daring hope for the conversion of all the nations to the worship of the true God it develops the most universalistic features of the Biblical prophetic tradition.” Reading Revelation as a call to action will be a big step towards seeing it as a teaching that should unite the Church in Christ-honoring solidarity rather than divide it into competing theological factions. The consolation Revelation provided to early Christian martyrs and the hope it offers for the final events of history are then united to its clarion call for the Christian to live boldly in the present age.

[1] Richard Bauckham, The Theology of the Book of Revelation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993).

Have not heard from you! Would love to see you soon.

Claire