In general, I don’t use this ministry blog to comment much on pop culture items, even though dissecting trends and themes within popular music, movies, and television shows is stock-in-trade for many bloggers and writers on the internet. I feel there are plenty of other people out there who can talk about pop culture probably better than I could, and so often I guess I just don’t see the relevance of such discussions to my work in ministry. It’s interesting to engage with whatever is the latest hot cultural item, yet as most of us are aware, pop culture trends come and go with alarming rapidity, especially in the internet and social media age. What is trendy and current now might very much be “old hat” in a manner of just a few months. And even the best trend-watchers and media experts cannot really predict what will stick around and what will fade. For example, I’m sure there were many media pundits in the mid-60’s who assumed The Beatles were purely a teenage phenomenon, and would never have the lasting impact on Western society, let alone popular culture that they’ve had. So in general, I try to steer away from such cultural explorations, and focus more on foundational aspects of ministry and the Christian life that have stood the test of time.

All of that to say that this blog post is going to be about popular culture haha. Specially I want to share some personal reflections of mine after having recently seen the new Martin Scorsese film, “Silence.” Occasionally you are so touched by a film that it continues to play in your head for days and weeks afterwards, leaving indelible images, and perhaps more significantly questions and new perspectives on life. Certainly “Silence” proved to be such a movie for me. It’s already generated some share of controversy in the Christian community, but for anyone who hasn’t seen it yet, I’ll go ahead and urge you to do so. You might not like everything in the film, and certainly it is a difficult movie in parts to watch, but I believe that any thinking Christian will benefit from having to wrestle with some of the spiritual themes that emerge from Scorsese’s nearly 3-hour long historical drama. This post isn’t necessarily meant to be a straightforward movie review, but more just a series of reflections that I’ve been carrying around with me since seeing the film several weeks back. However a warning—this post will contain some significant plot spoilers, so if you haven’t seen the movie yet, perhaps watch it first!

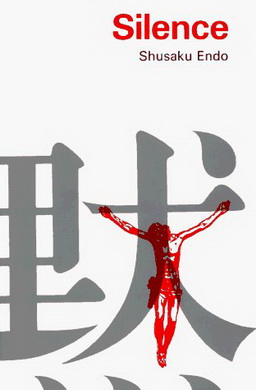

First—a little background information though. “Silence”, released in late 2016, is based on the 1966 novel of the same name by the Japanese writer Shusaku Endo. Endo was a practicing Catholic, and this is his most famous work, widely acclaimed by many as one of the outstanding novels of the 20th century. It is based on historical events surrounding the attempt by Portuguese Jesuit priests to evangelize Japan in the 17th century amidst severe state-led persecution. Director Martin Scorsese had been seeking to adapt “Silence” into a film from as far back as 1990, and described the project in strong terms as “an obsession…it has to be done.” Although he has always identified as a Roman Catholic and while some of his films have explored religious themes, Scorsese’s work has been equally marked by featuring high levels of profanity and violence. He has made films that have both been widely celebrated, such as the award winning Raging Bull (1980) and have courted considerable controversy, such as 1988’s The Last Temptation of Christ. But from the start of the movie, it is clear that Scorsese takes his subject matter seriously with “Silence.” As further proof of this, he arranged for the world premiere of the film to take place at the Vatican, where a special screening was arranged for Pope Francis and members of the Jesuit Order.

It’s also apparent that the main actor in the movie, Andrew Garfield, took his role very seriously. Garfield, who is part Jewish, had previously described his religious background as “mostly confused”. Yet in several interviews given around the time of the film’s release he makes some statements which would seem to indicate that he was spiritually changed by making the movie. Garfield plays Portuguese priest Sebastião Rodrigues, whose story is at the center of the film. In order to prepare for the role, he spent a year with a Jesuit spiritual advisor, whom he still considers to be a close friend. He practiced Jesuit founder St. Ignatius of Loyola’s spiritual exercises, and even spent time on a spiritual retreat in Wales. Talking about his experiences in preparing for the film role, in an interview given to America, a Jesuit magazine, Garfield noted–“What was really easy was falling in love with this person, was falling in love with Jesus Christ. That was the most surprising thing.” Later, he added: “It’s such a humbling thing because it shows me that you can devote a year of your life to spiritual transformation, sincerely longing and putting that longing into action, to creating relationship with Christ and with God, you can then lose 40 pounds of weight, sacrifice for your art, pray every day, live celibate for six months, make all these sacrifices in service of God, in service of what you believe God is calling you into.” In another interview with British paper The Guardian, Garfield reflected candidly on some of his disillusionment with the trappings of celebrity as a major movie star–“The poison in the water started a long time ago,” Garfield says, “with the birth of Hollywood and Edward Bernays, propaganda and PR. We’re all in the same position now, because we all have the ability to self-promote. People are rewarded with money and fame, and ultimately the correct amount of emptiness for an egocentric life. There’s part of me that will always want to shed all that.”

Now—let’s get into the content of the film itself. As I mentioned earlier, “Silence” is a historical drama, based on actual events that occurred during attempts by Portuguese Jesuits to Christianize Japan in the 17th century. The faith had first been introduced to the islands starting in the mid-1550s with the work of the famous Jesuit priest St. Francis Xavier. After some initial successes, a strong native community of converts developed. However by the end of the 1500s, the official Japanese attitude towards Christianity had changed, and official persecutions began to take their toll. By the time of the movie’s setting in the mid-1600’s, Christianity is an officially outlawed religion. The movie opens with two Portuguese Jesuit priests, Sebastião Rodrigues (played by Andrew Garfield), and Francisco Garupe (played by Adam Driver) who are in Macau, a Portuguese-controlled city in China, and are seeking news of Cristóvão Ferreira (played by Liam Neeson), another priest who had been their mentor in the faith, and has now been working as a missionary in Japan for many years. The Jesuit Order fears however that Ferreiera has committed apostasy, because they have not heard from him in some time, and they know that the persecutions taking place in Japan are increasingly severe. Nevertheless the two young priests boldly volunteer to be sent to Japan in order to find out what exactly has happened to Ferreira. Their supervising priest warns them sternly—“the moment you set foot in that country, you step into high danger.” In a back-alley of Macau, the priests find Kichijiro, a Japanese fisherman who knows some Portuguese and agrees to be their guide as they take ship for Japan.

Upon arriving in the islands, Rodrigues and Garupe are surprised to find a fairly large underground church composed of native Christians, who continue to practice their faith secretly, despite the great risk posed by the state persecution. In a series of touching scenes, the two priests experience overwhelming love from these beleaguered believers, who have been desperately awaiting spiritual guidance. The priests perform baptisms, hear confessions, and administer communion. In one particularly heart-wrenching scene, the native Christians insist the priests eat from their meager stockpile of food. When asked if they too will eat, one of the believers responds “you are our food.” But despite this warm reception at the hands of the native Christians, the two Jesuit priests recognize they are in grave danger as well. They must hide during the day to avoid detection, and can only come out at night to minister to the people. It is but a matter of time though before the authorities catch on their presence. Soon an official government detachment comes to the village where they have been working, in order to search for any suspected Christians. The villagers are told that a substantial cash reward will be offered to anyone who turns in a suspected believer. The detachment returns a few days later and this time calls out the names of several individuals who they accuse of being secret Christians.

Then they produce a crudely made image of Christ, called a fumi-e. The test proposed is simple. If an individual in question is willing to tread on this image, they are set free. If they refuse, they are arrested for the illegal practice of the Christian faith. In scenes that will be repeated many times throughout the film, the reactions of the suspected believers vary. Some decide to tread on the image to spare their lives and maybe save the village from further trouble. Others cannot bring themselves to dishonor Christ, and thus by their refusal, they ensure their arrest and probable death at the hands of the state authorities. As for the government officials themselves, their tone is often strangely conciliatory. They simply desire to preserve law and order, they say, and they even downplay the significance of the fumi-e, saying that to tread on one is but a symbolic gesture that will appease everyone. But for those Christians who refuse to tread, a terrible fate awaits. As Rodrigues and Garupe watch from a hiding place in horror, several Japanese Christians, including a very elderly believer are placed on crosses in the shallows of the ocean, and left to slowly drown and starve as the tide advances. Their bodies are then cremated so that they cannot be given a Christian burial. Nonetheless even amidst this traumatic scene, the faith of the native Christians shines through. One of the dying men continues to sing praises to God for several days until his body finally gives out.

In the aftermath of this wave of persecutions, the two priests make the difficult decision to leave the village, believing their continued presence there might cause more harm for the remaining believers. Rodrigues and Garupe then separate to try and reach further villages and assess the state of the believers there. We gradually find out more of the backstory too for Kichijiro, the fisherman who had guided the two priests to Japan from Macau. It turns out that he too is a Christian, but one who had recanted his faith in order to save his own life during an earlier period of suffering. During this persecution, the rest of his family were all martyred. As a result, he is wracked with guilt, and is continually wanting to confess to Rodrigues and ask God for forgiveness. At one point in the film he wonders aloud about what place there is in the Kingdom of God for a weak man such as he is. But while Rodrigues tries to comfort him, Kichijiro it seems cannot resign himself to be fully committed believer amidst the threat of persecution that continues to swirl over his head. In a haunting scene, the gaunt and thirsty Rodrigues, wearied by his long journey asks his native guide to find some water. At first the priest is relieved upon seeing the fresh stream, and then as he begins drinking, he becomes positively joyful, for there, for an instant, reflected in the water he sees an image of the face of Christ staring back at his own. A British movie review from The Guardian was rather critical of this moment in the movie—“there is something a little broad about the moments in which a priest sees visions of Christ in himself.” But for me it remains one of the defining moments of the film In Roman Catholic theology, the priest is considered to be acting in persona Christi. In other words, as he ministers to his congregants, he is standing in the place of Christ at that moment. And even as a Protestant, I think this is a valuable spiritual concept, especially if it is broadened in scope. After all, the term “Christian” itself means nothing more than “little Christ.” All of us then as believers have the opportunity to be Christ to someone else on a regular basis, mirroring the attitudes and actions that Jesus would take were He present. And of course given Jesus’ promise of a continual presence with us from Matthew 28:20, there is added reason for us to seek to always represent Christ in whatever situation we find ourselves.

Rodrigues is rejuvenated by this sudden appearance of Christ’s face following a difficult period of doubt for him, but the vision is placed into the full and proper context with the next scene. For right after leading him to the water, Kichijiro is promptly surrounded by a group of imperial authorities, one of whom throws pieces of silver to him. It is clear then that he has betrayed Rodrigues, solidifying his reputation as somewhat of a Judas figure in the overall arc of the story. And yet, as the film unfolded further, I increasingly found myself identifying with this wretched man, because after each failure we see his despair, and heartfelt desire to repent. I believe that Scorsese is trying to show us that there are those who want to follow Jesus, but are simply too weak to remain resolute when savage persecutions become the litmus test for true faith. Perhaps given similar circumstances, many of us would react the same way. As for Rodrigues, perhaps he has discovered that the face of Christ appears to us most clearly in moments of need and of suffering. For after having witnessed Jesus in the pool of water, he is about to now enter into the very darkest of nights of the soul.

In stark opposition to Kichijiro’s weakness however, is Father Garupe. Rodrigues, after being arrested and taken to Nagasaki, is later brought out to a cliff overlooking a beach. In the distance he recognizes Garupe along with several other native believers. After refusing to recant, the whole group is drowned. Garupe perishes, exhausted in a last desperate act of Christian sacrifice, as he tries to hold one of the condemned women up in the water. This glorious martyr’s death is perhaps what Rodrigues has in mind for himself, disheartening though it is for him to witness his one other companion’s demise. But now the film zeroes in on the personal drama that is about to unfold within the very soul of this priest as he at last comes face to face with the authorities, and with the full consequences of his decisions regarding his faith.

Rodrigues, while imprisoned in Nagasaki, witnesses several more instances where suspected native Christians are asked to tread on the fumi-e. Some do, but others refuse, and although the authorities don’t always react immediately, in one particularly dramatic instance, a believer who does not tread is promptly beheaded on the spot. This graphic execution underscores the intense moral dilemma that is now raging within Rodrigues. On the one hand, he intends to stand firm in his faith, wanting to offer a good example for those Japanese believers who are prepared to die before they will renounce Christ. But at the same time, it soon becomes apparent that the Japanese authorities are using Rodrigues as a pawn. They have no intention for the time being of killing him and thus allowing him to become a martyr, and they don’t even torture him. Instead, his punishment is to have to watch native Christians being interrogated before the fumi-e, as well as later being tortured by being hung upside-down in pits. Rodrigues also has periodic conversations with the head of the government interrogators, an old Japanese nobleman known as the “Inquisitor”. He regards Rodrigues with some disdain, seeing him as a proud man who is arrogantly determined to bring in a foreign religion to Japan. As he discusses the state persecution of Christians with Rodrigues he notes severely–“the price of your glory is their suffering”

Still, Rodrigues remains resolute, until he faces his greatest test. He is brought to a Buddhist monastery, and there he at last comes face to face with Father Ferreira. His former mentor has now adopted a Japanese name, has married a Japanese woman, and is studying Buddhism. All of Rodrigues’ worst fears have been realized. At first he reacts with great anger, calling Ferreira a disgrace to the priesthood. Yet Ferreira, (played convincingly by the veteran actor Liam Neeson), responds calmly. He explains that after being tortured, and witnessing the suffering of so many native Christians, he committed apostasy. He states furthermore his conviction that Christianity is alien to the Japanese mind and culture, and will never be able to take long-term root in the country. Let down by the last man he hoped he could place trust in, and despairing of ever being able to leave the prison, Rodrigues is subjected to one more harrowing evening of listening to native believers being tortured as they are hung upside-down. Then, shockingly he is told that these are people who have already apostatized. But they continue to suffer because the authorities have realized that the single most demoralizing blow they could deal to the Christians would be for them to witness the apostasy of their leader, the priest. And so Rodrigues is told that he can end the suffering of these individuals only through his own renunciation of the faith. A fumi-e is brought out, and Rodrigues is told to step on it. Then in perhaps the single most dramatic moment of the film, Christ, whom he has been waiting to hear from for so long, finally speaks. “Trample!” the voice of Jesus says. “It was to be trampled on by men that I was born into this world. It was to share men’s pain that I carried my cross.” So Rodrigues steps.

Then the movie fast forwards several years. We see Rodrigues now having ostensibly followed the same path of apostasy as Ferreiera. He has married a Japanese woman, taken a Japanese name, and is even shown in one scene working alongside his former mentor, helping the governmental authorities to sort through religious iconography captured from suspected Christians. There is also a heartbreaking reappearance by the disgraced former guide and betrayer Kichijiro, who now works as a servant for Rodrigues. At one point he begs him for forgiveness and absolution, but with an air of great sadness, Rodrigues refuses, saying simply that he is no longer a priest. The movie concludes with a few more poignant scenes. Kichijiro is caught with a Christian amulet, and despite his claims that he unknowingly won it from gambling, he is led away by the authorities, his final fate to be unknown to us. But perhaps this time, he will refuse to recant, after so many past failures of faith and nerve. The most touching scene is saved for the end though. We see Rodrigues in the moments following his death, dressed in Buddhist robes and being prepared for a traditional Buddhist funeral. To all visible evidence, this is a final proof of his failure as a priest, as a missionary and as a Christian. He is be buried in the faith of the very religion that he came to Japan to counter. Or is he?? For furtively, and almost unnoticed as she ritualistically mourns the death of her husband, his Japanese wife quietly slips a sheath of white paper into Rodrigues’ coffin. Scorsese masterfully keeps its contents a secret, until almost the very last frame of the film. And there, as Rodrigues body begins to be cremated, we see that within the sheath is contained a small crucifix, of the same kind which had been given to him by a native believer when he first came to Japan.

Having described the basic plot art of the film, I want to share now in a few reflections. I can remember that in the immediate aftermath of the movie’s conclusion, there was almost total quiet in the theater, rather than the usual chatter which begins as the credits roll. I left the theater trying to hold back tears, and with both a strange mingled sensation both of heaviness and exultation in my heart. What to make of this extraordinarily complex, and haunting piece of cinema?? I’m still wrestling with those questions several weeks later. I certainly understand why this is a controversial movie, and why some Christians may find it unpleasant and disturbing. That does not mean however that the movie is unbiblical. In fact, I would assert that it confronts us, as comfortable 21st century American Christians with some very hard Biblical truths—mostly in the form of the questions that it raises. Like a gifted filmmaker, Scorsese, I believe, is ultimately less interested in providing concrete answers to all these questions (a fact which alone will upset some moviegoers who like neat, tied-up endings) than he is in forcing us as the viewer to squirm in our seats as we contemplate the way we may have reacted in a similar situation. And yet “Silence” as a movie is not so open-ended that we are merely left in confusion. In fact, taken as a whole, it provides a narrative which for me confirms some of the essential, and unchanging facts about who Jesus is, and who we as His followers should be.

So I’ll now try to unpack some of these thoughts. Let’s think for a minute about four of the main characters—Rodrigues, Garupe, Ferreira, and Kichijiro. If Garupe’s martyr’s death represents a more straightforward expectation of the resolute faith of a missionary prepared to sacrifice his life for the Gospel, what do we make of the ragged inconsistency of Kichijiro’s testimony, and his continual recanting, even to the point of betraying his friend Rodrigues, followed by tearful pleas of repentance? Well, both are Biblical figures. Because for every Stephen that comes out of the pages of Scripture, dying steadfast in his commitment to Christ, there is a Judas, or perhaps more accurately a Peter. Because the leader of the Apostles, the man who first proclaims Jesus as the Christ, we must never forget, is also the same man who denies Jesus three times with a curse. Kichijiro’s continual weakness in the film then serves as a reflection of the spiritual inconsistency that we all struggle with. It is embodied by Paul’s impassioned words in Romans 7:19—“For the good that I will to do, I do not do; but the evil I will not to do, that I practice”. Jesus knows we are prone to such failings all too well—as He tells the sleeping disciples in the Garden in Matthew 26:41—“Watch and pray, lest you enter into temptation. The spirit indeed is willing, but the flesh is weak.”

Rodrigues and Ferreira are even more complex as characters though. It would be easy to simply dismiss them both as failed missionaries, as apostates, who cracked under the pressure of persecution and then renounced their beliefs in order to live a comfortable and assimilated life in Japan. While there is some truth to this, I don’t think such a simplistic view captures the whole story, especially in the case of Rodrigues. First of all, neither man gives in so easily. The very opening scene of the film actually shows Ferreira witnessing native Christians being tortured by having boiling water poured over their bodies, in a terrible, blasphemous mockery of baptism. We later see scenes where Ferreira himself is tortured in the same upside-down manner that Rodrigues later witnesses native Christians suffering at the Nagasaki prison. Ferreira reveals that he spent 15 years trying to convert the Japanese amidst all of these persecutions. Rodrigues of course goes through his own intense struggles as we witness throughout the film. At the outset of his landing in Japan, he is overwhelmed at the sheer challenge of trying to bring Christian comfort and leadership to the scared, scattered Japanese believers. Then he suffers untold agonies at having to watch these Japanese brothers and sisters in Christ tortured while he is powerless to help them. Finally there is the excruciating pain of coming face to face with Ferreira his former mentor in the faith, and the man whom he had come to Japan in order to find—only to discover that he is now apparently an apostate. Throughout all of this, I think that the filmmaker Scorsese wants to show us that committing apostasy is not a hasty act born out of a quick desire to avoid suffering, but something which can be brewing inside one for years, and is eventually brought out by a combination of circumstances. In the end, with both Ferreira and Rodrigues and their decision to recant, the tipping point actually seems to be less about them wanting to end their own suffering, and more about wishing to help end the sufferings of native believers.

This brings me to perhaps the most controversial part of the movie. When Christ seemingly speaks to Rodrigues, giving him permission to step on the fumi-e, is it really the voice of Jesus? Would Our Lord ever tell us that in effect, it’s ok to give in to persecution, at least on the surface?? I certainly cannot know for sure, nor do I think Scorsese completely wants us to know, that the voice Rodrigues hears is truly that of Jesus. But how could it be that Jesus might conceivably say such a thing?? I am reminded of one particular passage in Scripture found in Luke 22:21-34. It is just before Jesus is to face His betrayal and arrest in the Garden of Gethsemane. And He turns to Peter, seemingly the leader and one of the most trustworthy and faithful of all the Disciples, with this shocking prediction—“Simon, Simon! Indeed, Satan has asked for you, that he may sift you as wheat. But I have prayed for you, that your faith should not fail; and when you have returned to Me, strengthen your brethren.” Peter then protests vehemently: “Lord I am ready to go with You, both to prison and to death.” But Jesus responds: “I tell you, Peter, the rooster shall not crow this day before you will deny three times that you know Me.” Of course Peter shortly thereafter fulfills Jesus’ prophecy, as fear leads Him to a threefold denial of the man he claimed he was ready to die for. Later however in John 21, we find Peter being forgiven and restored by Christ. So what does this have to do with the denial of Rodrigues, and the apparent voice of Jesus speaking to him during that final test of faith before the Japanese officials with their fumi-e?? Is Jesus saying that it is ok to have a failure of faith?? Well yes—in the simplest terms, but we need to unpack this idea a little further. Because Jesus saying that it is ok when we fail is very different than Him endorsing our failures or weaknesses. But just as Christ recognized that Peter would shortly fail Him, and yet not ultimately be lost to Him, and maybe He sees the same thing in the heart of Father Rodrigues.

One of the bedrocks of my theology as a Southern Baptist has been the concept of “once saved, always saved”, sometimes known in other theological terms as “perseverance of the saints.” There are many Scriptures we could cite in support of this idea that once someone places their faith in Christ, it is impossible for them to later lose their salvation. Two of my favorites are John 10:27-29—“My sheep hear My voice, and I know them, and they follow Me. 28 And I give them eternal life, and they shall never perish; neither shall anyone snatch them out of My hand. 29 My Father, who has given them to Me, is greater than all; and no one is able to snatch them out of My Father’s hand.” and also Philippians 1:6—“being confident of this very thing, that He who has begun a good work in you will complete it until the day of Jesus Christ” The most compelling reason though for me to endorse the idea that Christians can’t lose their salvation is tied back to another foundational part of my theology, the idea of salvation by grace through faith alone, as expressed in Ephesians 2:8-9—“For by grace you have been saved through faith, and that not of yourselves; it is the gift of God, not of works, lest anyone should boast.” Thus if faith is something that can be lost, it seems like we are putting it into the category of a work, and also saying that salvation is not a certain thing, but rather depends on one’s current spiritual state. Ultimately, I don’t believe ultimately that Scorsese is trying to tell us that Father Rodrigues’ recanting leads to the damnation of his soul. After all, that poignant final scene of him holding a cross in his grave, one that was put there by his wife, suggests to me that Rodrigues remained a Christian, at least secretly, and that he more likely than not also raised up his Japanese family to be believers.

But putting aside for the moment questions of Rodrigues’ eternal destination, I know there are those who will still scoff at the idea that Jesus would ever give anyone permission to experience a lapse of faith, even it was merely in a symbolic fashion that Rodrigues treaded on the fumi-e, while keeping faith in his heart all along. Now certainly, we’ve seen historically how persecution can fuel growth in the church, from the earliest days of Roman Christians dying in the Coliseum, to even the 21st century, with the explosion of the underground church in China, and the continued growth of the church amidst severe persecution around the Middle East. Longtime Southern Baptist missionary Nik Ripken, is one of the world’s leading authorities on the persecuted church, and a man who spent much of his missionary career working amidst believers who faced grave and life-threatening consequences for making a profession of faith in Christ. He consistently writes and speaks of the value of persecution, even going so far as to question why we, in the West will pray for an end to it, when it has proved to be such a catalyst for church growth through the ages. And indeed at one point in the movie, Father Rodrigues even states “the blood of martyrs is the seed of the church.” So once again—how could Jesus ever advocate anything other than a believer continuing to endure persecution, and be faithful to the end?? I cannot give a definitive answer, but only offer a few observations. First, it is clear from the experiences of Ferreira, and then Rodrigues, that neither man “cracks” under the pressure solely of their own persecution. They both endure great suffering, and in particular Rodrigues, from the start of the film, by volunteering to be sent to Japan, must know that he could well be faced with possible martyrdom. But I sense that the real pain both men experience is from having to witness the suffering of Japanese believers, and knowing furthermore that their refusal to recant will cause even more native Christians to suffer.

Does this justify apostasy? No—but it does help us to put their decision into a little bit more context. It is also at least a valid question to raise as to whether merely treading on an image changes what is in one’s heart? Now I realize of course that we are commanded to confess Christ not merely in the privacy of our own spirit, but in the public sphere, and certainly the public treading on the fumi-e by the very priests who the native Christians most revered would have had a devastating effect on the morale of the Japanese church—much as the authorities intended. So I’m not attempting to endorse the actions of these priests, but I’m also not prepared to say that they committed a permanent or unforgivable apostasy. I once shared in an earlier blogpost about why I keep a crucifix on my bedroom wall. For me it is a symbol of the burden, the suffering, the shame, the sin that Christ not only carried for me, but is still carrying for me. Jesus never endorses my sin, or gives me license to indulge my fallen nature. And yet He also stands ever ready to forgive me, no matter what I’ve done. So like Peter, and like Rodrigues, our failures of faith are seen and even understood by Christ as part of the reason for why He had to carry the heavy burden to Calvary. So if the voice of Jesus does indeed speak to Rodrigues to say “you may trample” it is perhaps the greatest demonstration of His overwhelming love and compassion for us, even in our miserable and wretched state of sinfulness. I refer back to an earlier comment I made about the Japanese convert Kichijiro, he who recants repeatedly, and ultimately betrays Rodrigues to the authorities, yet still wants to believe. He wonders what place there is for a weak man in God’s Kingdom. But Jesus came to the world to die precisely so that even the weak could find a place in the Kingdom of God. Thus I must conclude that even the very public failure of Father Rodrigues to declare his faith in front of the authorities, is covered by the blessed truth that Our Lord reveals to Paul. For Paul too, lest we forget is a man of profound weakness. He admits as much in Romans 7:19, and I have to imagine he lives his entire missionary career with some of the guilt and shame that remain from his not only failing to profess Christ, but from his active role as an agent of persecution towards the church. And yet Jesus promises to him in 2 Corinthians 12:9—“My grace is sufficient for you, for My strength is made perfect in weakness.” Scorsese’s film invites us to wrestle with, and ultimate accept that spiritual paradox, whatever it may mean for each of us individually.

The movie’s title derives from the fact that for much of the film, Rodrigues complains of the fact that he seems unable to hear from Jesus. At one point, his heart brimming over with despair, he exclaims—“I pray, but I’m lost. Am I just praying to silence??” But as we have noted, Jesus breaks His silence at the moment Rodrigues finally is brought before the fumi-e. Similarly, the face of Christ appears to him just before his own betrayal and arrest at the hands of his Japanese guide and friend Kichijiro. I think that Scorsese is making a twofold statement here on the nature of how and when God chooses to speak to us. Certainly the Lord can communicate through the Holy Spirit and Scripture and a whole host of other mediums, and at different times and seasons in each individual life. But He also chooses to speak uniquely to us in times of suffering and ironically enough, in those periods of life in which we seemingly are unable to hear His voice—in the silence itself. God speaking through silence is in large part the theme of the Book of Job. Job doesn’t hear from God until the very end of the book, and even then, he never really gets his big “why” questions answered. And yet we sense that the message of Job is that we must learn to accept it when God doesn’t speak, and realize that does not indicate His absence. Or consider Esther. God’s name is never actually mentioned throughout the entire book, and yet clearly it is a story of His working “behind the scenes” and through His servants to foil a Persian plot of destruction against the Jews. Jesus’ life is certainly marked by those moments where God would appear to perhaps be silent—His time of temptation in the desert, His agony in the Garden, and most notably, His cry of desertion, uttered on behalf of all humanity at the Cross in Matthew 27:46—“My God, My God, why have You forsaken me?”

So this movie reminds us that God can, and does speak through those moments of silence. It also reminds us that God, especially through the person of Jesus Christ, does not just pity us in our suffering and weakness, but actively suffers alongside of us in difficult moments. In Revelation 21:7 we are promised by God—“He who overcomes shall inherit all things, and I will be His God and he shall be My son.” “Silence” as a movie, invites us ultimately to question ourselves—what would we do, and how might we react, if we ever faced anything even remotely like the kind of persecution that Ferreira, Garupe, Rodrigues, and the countless Japanese Christians in the 17th century were confronted with? And so while some will remain critical of the film’s central characters, and the decisions they made amidst very trying circumstances, I for one, from the relative prosperity and comfort of the American church, hesitate to cast too strong a judgment on those men, into whose hearts I certainly cannot see or definitively judge. As I continue to reflect on this movie, I’m drawn towards thinking about not only how I might respond to persecution, but all of the ways in which I currently fail to stand up for Jesus and make spiritual compromises, even while living in a place of physical safety, religious liberty, and economic prosperity such as many other brothers and sisters in Christ have never known. I think the bottom line is that if we are prepared to label a character such as Father Rodrigues as an “apostate” then we are all apostates. But even amidst the flames of this world, and every effort to shake and buffet our faith, we will hold fast to the cross, somehow, and someway even as does Rodrigues, clutching it in his dying hands in the film’s final frame??

I love “Silence as a movie because it doesn’t offer us easy answers; in the process recognizing and treating with appropriate complexity the subject of persecution, and how that can affect churches and Christians who, in the final analysis remain flawed and human. But as I believe the movie demonstrates, these flaws, if acknowledged, and repented of, ultimately draw us closer to the eternal embrace of the God whose arms are stretched wide for us in pain, but most importantly in love, at the Cross. Maybe the greatest truth expressed in “Silence” is one unspoken in the film’s actual dialogue, but very apparent in its entire ethos and message. The truth that Calvary provided the last possible Word on how much God loves us, how willing He is to suffer with us, and that indeed, His work is finished, as it relates to earning our forgiveness, acceptance, and salvation before the Father. So in those moments of spiritual silence that have followed for the church down through the ages, and in the moments of silence which will surely come for each one of us as Christians, we can have confidence that God remains by our side with a love that no amount of speaking could ever express any clearer.